|

IUR - March/April 1991 |

| published by CUFOS - The Center for UFO Studies | |

I Remember Blue Book

Jennie Zeidman, author of A Helicopter-UFO Encounter Over Ohio (1979), is a CUFOS board member and a contributing editor to IUR.

The dark recesses of the CUFOS archives have yielded up a paper titled Report to Stork on Blue Book Henry, The by-line is my own; the date is August 1953.

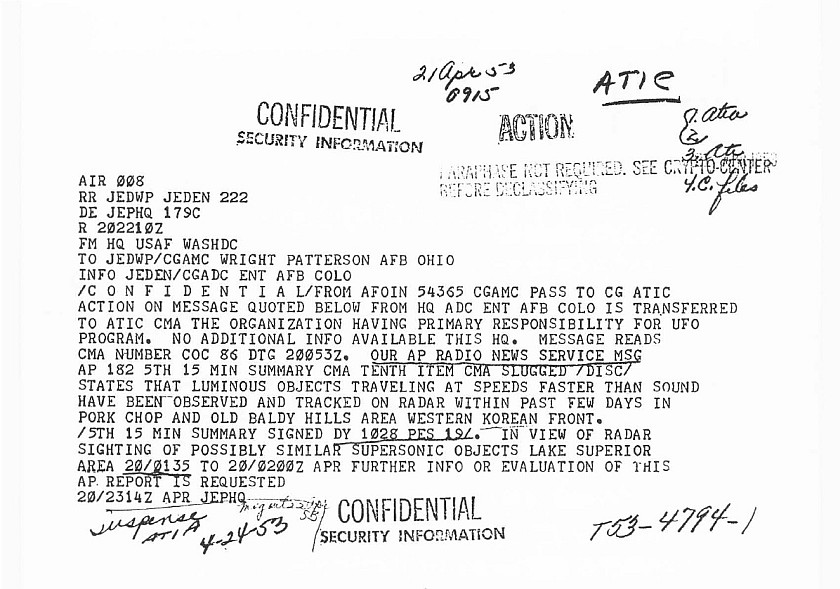

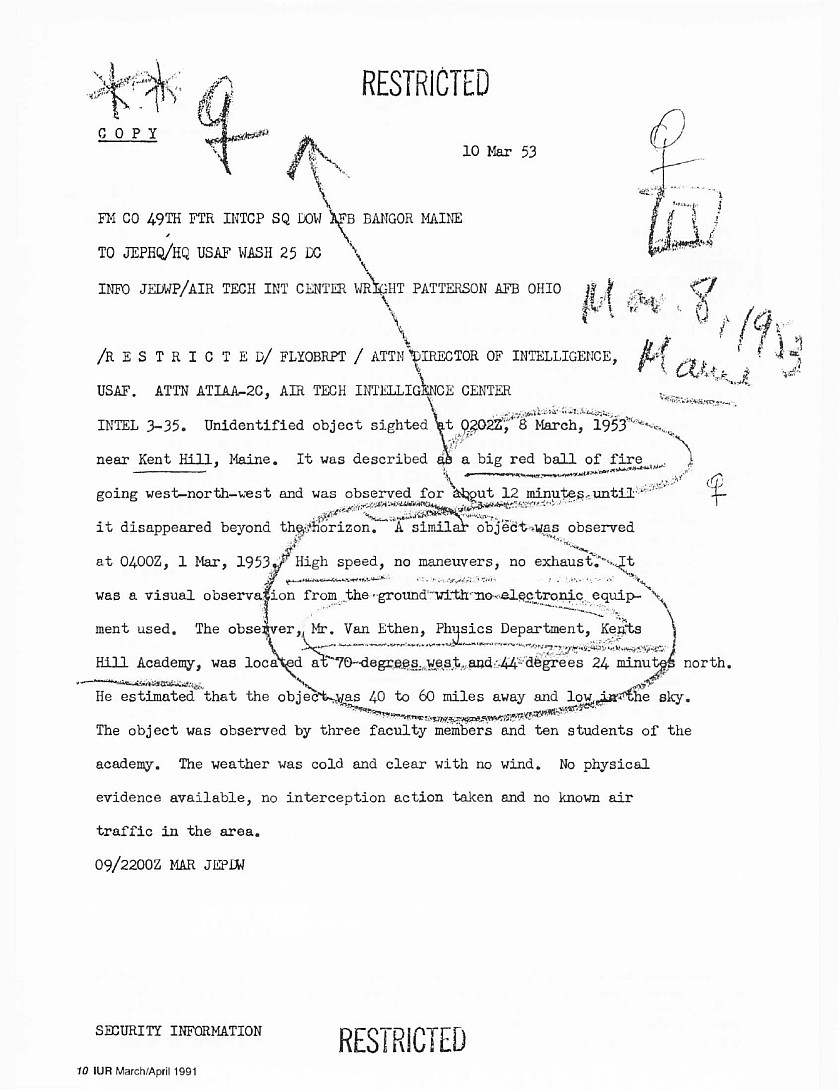

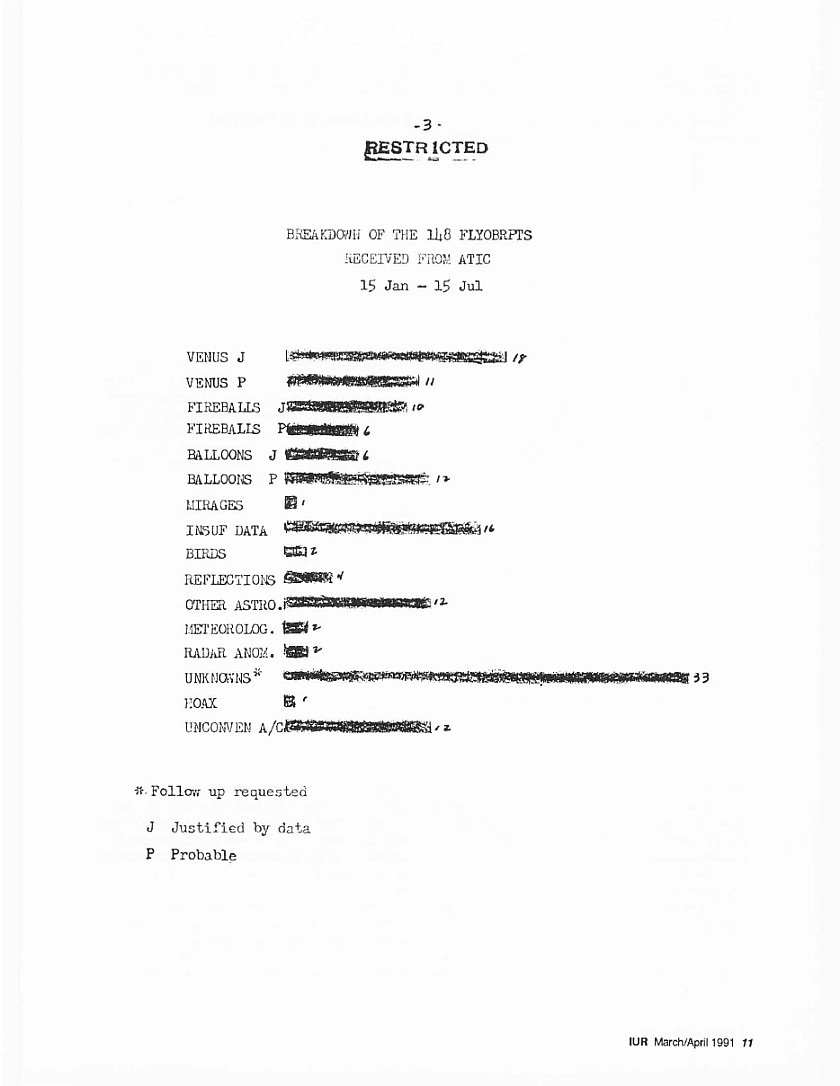

The document is a compendium of 148 “FLYOBRPTS” (flying object reports) and their cursory analyses as they passed from the Air Technical Intelligence Center (ATIC) through the hands of J. Allen Hynek (and me) between January and July 1953. (See illustrations 1 and 2 for examples.) The report also summarizes correspondence with the 35 amateur astronomical societies, 19 Ground Observer Corps Filter Centers, and 48 CAA (now FAA) Control Towers which were contacted with the objective that they would or could provide corroborating (or disconfirming) information for the official reports, specifically with regard to phenomena such as bright meteors/fireballs, normal aircraft, or meteorological phenomena.

The report itself is of little import. The Air Force favored astronomical answers, and Hynek was able to provide many from the selected raw reports presented for his analysis. (See bar graph.) The extremely high number of unknowns (22 percent) and cases of insufficient data (another 10.8 percent) reflect not so much the high strangeness of the information presented as the inadequacy of the reporting mechanism. One paragraph of teletyped tidbits was supposed to provide enough information for a justified, probable, or at least possible identification. Of course it couldn’t be done. 1 don’t recall our criteria for differentiation between “unknowns” and “insufficient data.” The only certainly I can see in perusing this report is that Venus was in eastern elongation during that time period and that lots of people, even those from college physics departments, couldn't identify it.

Of greater interest than the report may be some associated memories of those heady times: the convolutions of funding of UFO research, the desperate emphasis on hush-hush amid an environment of ludicrously slipshod security, and the unfolding mystery of where Hynek’s consultancy to the Air Force on Project Blue Book really fit into the larger scheme of the UFO hierarchy. Enlightening discussions of these matters appear in Hynek’s The Hynek UFO Report. (1977) and David M. Jacobs’ The UFO Controversy in America (1975). The remarks that follow reflect my personal involvement and interpretations as Hynek’s assistant between 1953 and 1956.

Project Stork

Let us start with Project Stork. I doubt, 38 years later, that I'll ruffle any feathers with that name. Heaven knows, it’s been mentioned in print, and from time to time I’ve come across persons (there must have been thousands of us, worldwide) who worked on various phases of it. The fact is that the mission of Stork was to ascertain the capability of the Soviet Union to engage in technological warfare. The specific interest for our purpose is that the group at Battelle Memorial Institute which produced the (in)famous Project Blue Book Special Report 14 was associated with Project Stork. Okay, let’s not beat around the bush. Special Report 14 was a product of Project Stork.

Does that mean that the government thought UFOs might be Soviet technology? Or does it mean that the government already knew (five years after the Roswell incident) what UFOs represented, wanted to see what the Stork statisticians came up with, and then made sure that the “analysis” met with government “standards”? (Shades of the Condon Committee 15 years later.)

The answer is: probably not. The Condon Committee’s blatant objective was to pacify the public, whereas Special Report 14, within Battelle/Stork, was Top Secret. It didn’t need to be created (for public consumption) if the answer was already known — in other words, that the empirical characteristics of UFO reports were statistically different from those of reports that were ultimately resolved into mundane phenomena. Or was Stork perhaps merely a convenient funding vehicle for 14, a legitimately asked question, a relatively small effort that could be justified (or hidden) under the scope of the Stork mission? Regardless, Battelle was the right place for the work to be done. It is a superb group of scientists and engineers scrupulously devoted to excellence.

Battelle’s involvement with the fringe subject of UFOs was therefore a source of great embarrassment to it — a family secret, a skeleton in the closet equivalent to Grandpa’s alcoholism or Uncle Ray’s penchant for little boys. One absolutely did not mention Battelle in connection with UFOs. And since I had no need to know, the fact of this involvement (in spite of my Secret clearance) was kept from me for over a year.

In the spring of 1987 I found myself at a dinner party seated next to a Battelle executive — an old timer who I knew had worked on 14 as a member of Project Stork. I asked him if after 34 years he had anything he wanted to say about it.

My question made him uneasy. “We were concerned,” he said. He was referring to the data and to the Battelle scientists' interpretation of those data. He was referring to the thoughts of his fellow scientists on the question of “What are UFOs?” “We were concerned,” he said, and he would say no more.

Project Henry

During the first month (January 1953) I worked for him, Hynek went to Washington to attend the meeting of the Robertson Panel. He was an associate member, a second stringer, which was odd because he had been working directly with the data for about five years. I remember his return on a cold, wintry day. I expected him to announce there would be a major scientific undertaking on the subject. Instead, he told me, “They’re not going to have a scientific investigation. For some strange reason they voted it down. They didn’t even take a decent look at the data, and they decided to discredit them.”

Perhaps he needed some levity that day when he looked up from his coffee and crackers and suggested that we should have a name for his consultancy project, “something that captures the idea that these things flit around the sky.” An old-time popular insecticide was called Flit, and its trademark showed a hand-pumped sprayer and, I believe, a harried woman who had just been scared by a bug. “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” she is shouting. Hynek latched on to the word Flit, and thus Project Henry was named (Flit being too obvious and Project Insecticide somewhat cumbersome). Readers familiar with Hynek’s sense of humor know I couldn't possibly have made this up.

This is the way Henry worked:

About once a week a courier from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (I assumed he was from Wright-Patterson) would arrive at Hynek’s office at Ohio State University with a manila envelope stuffed with TWXs—teletype UFO-sighting reports received from military facilities around the world.

Were they all of the reports Blue Book received — the total number it took in? Surely not. (Hynek often said he knew the best cases were withheld.) I usually looked them over before Hynek did. I had a Secret clearance by then (mid-1953), but only a few were ever classified beyond Restricted, and the sensitive material usually had to do with the installation or facility of report origin, not with the contents of the report per se. If Venus was in western elongation, there would be a whole slew of reports of a bright white light in the predawn east, and Hynek would chuckle and mutter about how darned uneducated the public was. When we would get a report of high strangeness, he would scratch his chin — beardless until the fall of 1953 — and say this might bear looking into. We would outline the information we wanted to have, and we would pass that on to Blue Book. But it hardly ever followed up for us. If we really wanted some information, we would have to go out and try to get it ourselves.

Hynek was paid to investigate only reports allocated to him by Blue Book. That meant that if we heard of a case in some other way—if someone called the observatory, say, or there was a newspaper story—we could not count it as an official case, and any expenses incurred by Hynek or me were not reimbursable. Many times we asked people to send a report in to Wright-Patterson so that a case we were already working on (privately) and had spent money investigating could become “official.” Sometimes it worked; sometimes it didn’t.

Hynek went to Wright-Patterson two or three times a month, and about once a month I went along. The Blue Book facility—building 263, not Hangar 18—consisted of three cramped, crummy little offices. The paint was peeling, and the file cabinets were warped. There were a United States map with pins stuck in it, a sergeant gofer, a gum-cracking, beehive-hairdoed secretary (a civilian), and a dried-out coffee pot on the window sill. This was before computers, of course, so the cases were filed chronologically. If you knew the date, fine. If you knew only the location, try the card index, and lotsa luck. No wonder I never saw Capt. Ed Ruppelt, the Blue Book head, smile. (I remember him as a by-the-book sobersides. I don’t recall a human side of him, even when we were having an informal lunch. But I seem to remember intense blue-gray eyes.)

In the early days of my association with Hynek, my title was research assistant, OSU department of physics and astronomy. I worked a few hours a day, spending about half my time on UFO matters and the rest as teaching assistant for Hynek’s undergraduate astronomy course and general Girl Friday for OSU’s McMillin Observatory. (I was also carrying 15 hours in my second-to-last undergrad quarter.) As the year progressed I graduated, my Secret clearance came through, I worked full time, and my UFO work increased proportionately.

The 1954 flap was underway, and one day I asked Hynek how it was that OSU was willing to keep me on as research assistant when most of my work was for ATIC.

“You’re not working for ATIC,” Hynek said. “You’re working for a contractor.”

I had no idea what he meant. “A contractor,” he repeated. “A contractor who doesn’t want to be known. But don’t worry about it. I’ve already told you too much.”

But 1 did worry about it. My paychecks said Ohio Slate University. The phrase “laundered money” was not in common usage in those days.

I stewed over this for a few days—not more than a week or two—and then the courier came with the weekly reports. Same man, same car—a Chevy that bilious shade of GI green. For some reason I walked him back out to his car, and did an incredible double-take as he drove away. It wasn’t a government car. It was his own car, with Ohio plates. This man’s initials were V.E., and the car license plate was VE-29. What a stroke of luck: a spook with vanity plates!

Furthermore, he was from Columbus. The local Chevy dealer’s name was on the license-plate holder.

Within five minutes I had raced over to the main OSU library, pulled down the Columbus city directory, and found the man’s name and his place of employment: Battelle. Confronting Hynek with my intelligence coup resulted in a few days of negotiations with Stork followed by an increased work load.

I went on a number of field trips for Henry, and the security situation was almost invariably deplorable.

Hynek arranged for me to visit astronomer Clyde Tombaugh at White Sands Proving Ground, New Mexico, during a trip I had previously planned for winter break 1952. (This was a private trip; I paid for it myself.) Tombaugh, who in 1930 discovered the planet Pluto, had himself experienced an extraordinary UFO sighting in 1949. A large, transparent fuselage wiLh lighted windows had sailed across his view as he enjoyed the evening in his backyard.

I arrived at White Sands after a cold and miserable pre-dawn bus ride from El Paso, and Tombaugh sent someone out to the gate to escort me to his office. We walked through hangars and offices and laboratories. “Oooh, what’s that?' I asked. There were rockets and fancy instruments and equipment lying all over the place. “That’s the new Nike,” my escort said, “and that one over there’s the Honest John.” I was carrying no documents to identify myself as affiliated with AUC. No one asked what kind of clearance I had. And at that time, December 1952,1 had none.

The fifth horseman

Hynek also arranged for me to meet with Lincoln LaPaz, the eminent meteoriticist at the University of New Mexico. LaPaz had been consulted by the Air Force during the spate of green-fireball sightings over the Southwest. It was common knowledge that he was interested in UFOs. (LaPaz is mentioned prominently in Ruppelt’s The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects [1956].)

I found LaPaz in his office at the university. I remember the formality of the room, he behind a large wooden desk, I in a straight chair at right angles. In contrast to the easy-going Tombaugh (and his family, who treated me to a Mexican lunch), LaPaz was a formidable presence, and I felt a bit uncomfortable. We discussed UFOs in general terms. He chose his words carefully, suggesting that the U.S. government knew plenty about UFOs. I brought him up to date on Hynek’s work and the general skepticism that I felt pervaded Hynek’s philosophy (and mine, too).

LaPaz listened to what must have been my naive jabberings. Then he pinned me with a solemn stare. “UFOs are the Fifth Horseman of the Apocalypse,” he said, and I was soon dismissed.

Pestilence, War, Famine, Death, and... ? As the years have passed, LaPaz’s chilling pronouncement has caused me growing concern. His name is not listed on the controversial MJ-12 document. But if such a group, or its equivalent, existed, he would have been a logical candidate for membership.

Back in Ohio the summer of 1953 produced a changing of the guard. For a few months Ruppelt was away, and Lt. Bob Olsson was in charge of Blue Book. At some time in that interval Hynek was going out of town, and he told me to expect a visit from some people from Wright-Patterson. Olsson (whom I already knew) came in, with the sergeant gofer and another man, probably also a lieutenant, to whom I was not even introduced.

It was a hot, stuffy day sans air conditioning. The soldiers took me into Hynek’s inner office at the observatory, and the lieutenant arranged the chairs: a straight chair in the center of the room—for me—and three other chairs at 10, two, and six o’clock positions. The anonymous lieutenant and Olsson faced me, and the sergeant sat out of my vision with a clip board and pencil.

They asked me how things were going with the project. What was Hynek’s attitude? What was my attitude? How did I like the work? What did I think of this case or that? My utter disingenuousness carried me through this ordeal. In my naivete I was probably even flattered to be the object of so much attention. In retrospect the third man reminds me of that nutty CIA man in the M.A.S.H. television series—the ludicrous paranoid who was forever finding devious plots in the most innocent situation.

I liked Bob Olsson. He often included his own evaluations and a friendly note on the reports sent to us, and I felt he was genuinely interested and conscientious in his work. Perhaps that’s why he lasted only a few months at Blue Book.

By mid-1956 Hynek had moved to Harvard for his worked (sic) on the International Geophysical Year, and I had moved to the main Battelle campus (about a mile from OSU) where my work for Stork also involved the IGY. The subject of UFOs was never mentioned.

Blue Book and beyond

Though I was officially removed from Blue Book business, Hynek and I continued to communicate regularly about UFO matters.

At midnight on March 26, 1966, my husband got me out of a shower for a call from Hillsdale, Michigan. It was Hynek, pleading with me not to get upset when I saw the morning papers. The Air Force had backed him into a comer. Say something, he was told. So he had said something. He had said that swamp gas was a possibility as a natural explanation for some lights over a marshy area, and the press jumped on it. The swamp-gas incident distressed him terribly because in effect the Air Force had forced him to compromise his scientific integrity.

Blue Book folded the end of 1969 following the publication of the Condon Report. Within a few months of the start of the Colorado project, Hynek had told me he knew it had been decided that the findings would be negative. For years he had understood that he was being kept out of the inner circle, that even with his high security clearances it was judged that he had no need to know what was really going on. He knew he had been used. He seemed actually relieved, then, when his Blue Book work was over. Now he was free to pursue UFO research from a purely scientific viewpoint without the restrictions imposed by his government contract.

But was Hynek’s government UFO work really over?

In October 1973 he called me to pick him up at Wright-Patterson and bring him to Columbus. It was the height of the Yom Kippur war, and Wright-Patterson was on highest security status because supplies for Israel were being flown from there. I took a wrong turn near the Air Force museum entrance and wound up driving out onto the perimeter of the field. I drove half a mile out on a taxi strip before I could turn around. No challenge. No one came after me.

I finally got reoriented and drove up to where I was supposed to pick up Hynek. It was a small one-storey building, and Hynek was standing in the doorway as I drove up. Another man appeared from the building. He was in dress uniform and may have been a major. I got out of the car, and Hynek made it a point to introduce me. Of course Hynek was always polite, but he easily could have just gotten into the car with no introductions. It seemed to me that the introduction was a purposeful act which I assumed had something to do with the fact that I was a UFO associate.

On our way to Columbus I asked Hynek in general terms what was going on. He would not tell me anything about what he was doing at Wright-Patterson. In face of his reluctance to explain, I felt 1 could not pursue the subject. But he was agitated on that trip and seemed preoccupied with whatever had occurred earlier that day. Of course Wright-Patterson housed other projects than those under the Foreign Technology Division,

But Hynek was working for FTD. Researcher Brian Parks has recently obtained, through the Freedom of Information Act, Hynek’s record of employment as FTD consultant from 1970 to 1974. He worked only a few days each year, but it was an ongoing consultancy, an executive appointment, beginning in April 1970, less than six months after Blue Book’s official closure. Was this work related to UFOs? At this point we still do not know.

On December 26, 1976, in the front third-floor office of the Hynek home in Evanston, Illinois, Hynek and I were talking theory as we had so many times over the years. Hynek was not a man to make bold statements, and I recognized the remarks of a man whose thinking had evolved with reluctance and deliberation over 28 years.

"It’s very definitely connected with intelligence somewhere,” he said, not with excitement and awe but with acceptance and resignation.